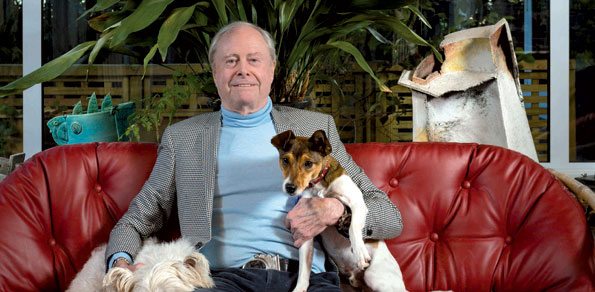

Lucinda Bennett explores one of the richest fine art collections in the country and talks to the patron behind it, Sir James Wallace.

Recently, I overheard someone say that “New Zealand doesn’t really do art— it’s just tikis and pohutakawa trees.”

The terrible thing about this statement is that, although untrue, it does reflect the way many of us kiwis regard the work produced by our compatriots. We don’t seek it out, we don’t talk about it over coffee and we aren’t proud of it. We think it is boring. We are wrong.

Even the most cursory delve into the Wallace Arts Trust Collection, a self-professed diary of New Zealand visual art, is proof of this.

What began with James Wallace’s purchase of a watercolour by Toss Woollaston back in the sixties has grown into a collection of over 6500 works, all by New Zealand artists except one: a Picasso etching that hangs above the door to his Conservatory. Almost every celebrated New Zealand artist of the past fifty years is represented in the collection. Rita Angus, Tony Fomison, Ralph Hotere, Pat Hanly and Len Lye, to name a few—there is even a McCahon hanging above the television in James’ living room, the running joke being that no one ever watches the television anymore.

At Rannoch, the four-storey Arts and Crafts style house where James lives amongst an ever-changing display of works from the Collection, I am overwhelmed not only by the volume of works on display, but by the diversity of them. Hanging alongside the works of New Zealand art royalty are many far stranger beasts, and it is these works that prove just how far from boring our art really is.

At Rannoch, the four-storey Arts and Crafts style house where James lives amongst an ever-changing display of works from the Collection, I am overwhelmed not only by the volume of works on display, but by the diversity of them. Hanging alongside the works of New Zealand art royalty are many far stranger beasts, and it is these works that prove just how far from boring our art really is.

They appear immediately as I enter the property, twenty small, orange jumpsuit-clad men appraising my car. These ceramic self-portraits make up Gregor Kregar’s I Appear and Disappear, a work that took two years to realise and which, when displayed as it is now, with figures lined up, hands in pockets, ominously watching my slow progress along the driveway, challenges the very way we look at art—we are not used to looking and being looked back at, least of all by the artist himself.

This unsettling first impression proves an apt introduction to Rannoch. Suprising, challenging works crop up constantly throughout the house and surrounding sculpture garden, an acre of ancient lava forest filled with corrugated iron elephants, manmade bones and doors to nowhere.

Inside the house, a painted perspex figure of David Bowie as Ziggy Stardust greets me at the door. I find Angela Singer’s bejewelled deers head, Deorfrith watching benignly over the stairs. A charming earthenware knicknack on the mantelpiece is revealed on closer inspection to depict Roy Horn being brutally mauled by his tiger. Upstairs, a serene purple Gretchen Albrecht that looks and feels like a spring evening seems at odds with the mass of ceramic sheep in rainbow jumpers that crouch before it.

When asked what attracts him (and he is obviously attracted, the Collection is full of them and so many are on display around his home) to these more idiosyncratic, playful works, James is circumspect. “Almost inevitably at an exhibition… the work which first attracts me – perhaps the most ‘beautiful’- is not the one I buy but instead I will settle for a less accessible and more challenging work which is going to last the distance.”

“Lasting the distance” is an interesting choice of words when we are talking about celebrity accidents being immortalised in clay, although as James rightly points out, “much of contemporary art now filters back to an audience ideas or things seen in the media, magazines or films – but in a way that has always been so.”

It seems that Wallace’s eye for the unusual and indiscriminate love of art in all its forms is what makes the Collection so remarkable, as is his desire to support emerging artists above all else, and his willingness to buy pieces because they are unexpected, because the artist is unknown. When asked whether he prefers art which is outwardly beautiful or art which is interesting, James, perhaps not so unexpectedly at this point, replies: “A work has to be ‘of interest’ first and foremost – an extension of a line, a slight deviation from what is expected, a form that somehow challenges what would be pleasing or expected. For me it has to be challenging for it to be interesting – beauty is often a by-product and beauty itself is most often found where others may not see it or where it is not expected through the then contemporary conduits.”

The Pah Homestead, TSB Bank Wallace Arts Centre

The Pah Homestead, TSB Bank Wallace Arts Centre

72 Hillsborough Road,Hillsborough Auckland 1042

www.tsbbankwallaceartscentre.org.nz / 09 639 2010 / enquiries@wallaceartstrust.org.nz

Open Hours: Tuesday to Friday 10am-3pm, Saturday and Sunday 10am-5pm (Same hours for the Pah Gallery Shop and the Pah Café) Group tours (from 8 – 18 people) of Rannoch may be arranged through contacting the James Wallace Arts Trust office. www.wallaceartstrust.org.nz

Article | Lucinda Bennett

Lucinda is a writer, theatre director and recent graduate of the University of Auckland with a degree in Art History and English. She is currently working as an assistant at Auckland Art Gallery, learning Te Reo Māori and working on her next play.

You can find her at lucindabennett.wordpress.com.

Photo | courtesy of Art Zone issue 50 July 2013 and Sam Hartnett